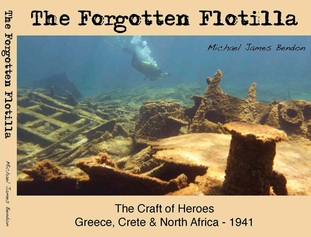

Tank Landing Craft Mk1

“She’s not exactly a thing of beauty. Then, he added: Keep it under your hat but it’s on the cards that the first batch of these things will be going out to the Middle East.” (Heckstall-Smith & Baillie-Grohman 1961, p. 69)

The Tank Landing Craft (TLC) Mk1 were prototype vessels, constructed in the latter half of 1940 by the British for Combined Operations. Churchill was keen to avoid another episode like Dunkirk where the retreating British armies had to leave behind all heavy equipment on the seashore. The Prime Minister saw these new vessels as forming the central element for amphibious operations in the Mediterranean.

The TLC Mk1s (‘A’ lighter) were developed and manufactured secretly with orders issued that forbade the taking of photographs of the vessels while under construction. At this stage of the war, Germany had yet to develop anything similar to these craft and apparently Britain hoped to keep it that way just a little longer. Readers may remember that during the invasion of Crete, German seaborne reinforcements had to be carried in an assortment of commandeered fishing vessels only.

The crafts’ real, and often unexpected, battle capabilities had yet to be tested. A Sub-Lieutenant from the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR), or perhaps only a Royal Navy (RN) Boatswain, skippered these ‘experimental’ vessels into the struggle in the Middle East. In fact, other than the crews of the TLCs themselves very few armed forces personnel had previously seen such vessels. “Indeed, not even aboard the flagship was there anyone who recognized them for what they were” (Heckstall-Smith & Baillie- Groham 1961, p. 55).

The new TLCs were the largest vessels of the landing craft types at that time. They were able to operate under their own power across long distances (900 nautical miles) and could carry up to six tanks or other heavy equipment.Built like a floating dock with sides, and two very powerful V8 engines, the craft were virtually unsinkable but were also very difficult to manoeuvre even in the slightest of seas. This led some aboard to speak of them as “Large Crude Targets”.

The first twenty Tank Landing Craft arrived in Egypt on cargo transports in early 1941 and immediately after reassembly took part in operations. The first five TLCs to be completed (TLC A1, A5, A6, A16 and A19) were sent from Alexandria on a supply run to the besieged town of Tobruk in early April. Upon arrival, they were immediately redirected to Suda Bay on Crete, where they were joined by two more TLCs (A15 and A20) sent from Alexandria. The TLCs were to be prepared to assist in the evacuation of Greece.

Only weeks earlier, Commonwealth troops had been sent into Greece to deter Italian and German forces from invading. However, the German assault proved too strong, and when the Greek military crumbled, there was no option for the British but evacuation. The harbour of Piraeus and the majority of other piers and wharves had been destroyed by the Luftwaffe. This meant that the withdrawing troops had to be picked up directly from beaches. This necessitated the use of small ship-borne landing craft as well as large TLCs, with their carrying capacity of 900 men, to ferry troops from beaches to the ships waiting further offshore. Greek fishermen also assisted in the dangerous task of ferrying the exhausted troops.

In total, six TLCs were involved in this operation, codenamed Demon, yet only one of them (A6) made it back to Crete at the end of April. Less than a month later, the Germans began their invasion of Crete with the deployment of huge numbers of paratroopers. This airborne assault proved costly in terms of soldiers lost, yet was ultimately successful. Again, the British were forced to evacuate.

By then, only two TLCs (A6 and A20) remained fully operational in Suda Bay and their skippers were ordered to make their way down to the southern coast of Crete to once again assist with evacuation. Neither of them was to reach their destination, as both were sunk off the coast at the northwestern end of Crete. It is only a matter of conjecture but had the TLCs, with their huge carrying capacity, made it to Sphakia in the south to assist, it is possible that a far greater number of the hard-pressed Australian and New Zealand troops could have been uplifted to safety.

Fortunately, none the crew of the two TLCs were lost in the divebombing attacks that sent them to the bottom, but all were eventually taken prisoner by German troops after being sheltered, at great risk, by many of the local villagers. They were then sent back to Germany. There they were to remain in a prisoner of war camp until the end of the war. The people of Greece and Crete continued their struggle against the occupation by Germany.

The remainder of the TLC Mk1s, The Forgotten Flotilla, remained stationed on the North African coast after being reassembled. They were assigned to the Spud Run, the supply run to Tobruk, and were incorporated into the WDLF (which likely stood for Western Desert Lighter Flotilla). Since the slow, unwieldy and poorly armed TLCs were often subjected to enemy attacks and sustained continual losses, the men assigned to them resolved the acronym in a slightly more grim fashion: “We Die Like Flies”.

Towards the end of the war, there seem to have been only three TLC Mk1s still in action, namely A4, A9 and A17. Although as yet unconfirmed, they may have been sent to Italy towards the end of the war.

There are now, unfortunately, few of the veterans of the Mediterranean campaigns left to tell their tales. If we were able to speak to more of them, many of their stories would likely include an encounter of some sort with a noisy, under-armed, flat-bottomed, slow-moving TLC and its hard-working crew. There would probably also be mention of the relief the craft carried and the solace the vessels brought.