8. Bibliography

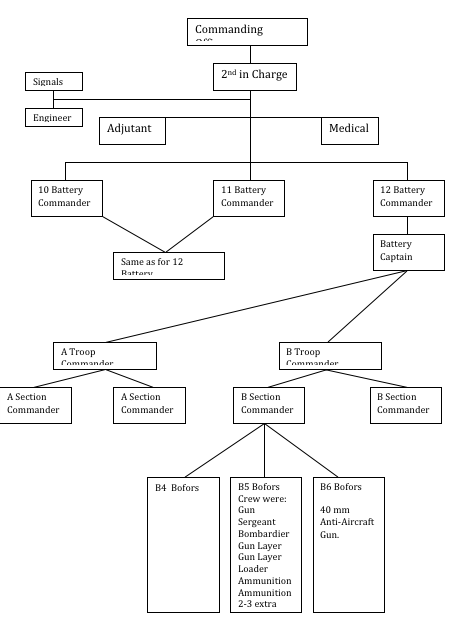

Australian War Memorial, Administration Instruction No. 12: October 21: 4th Australian LAA Regiment. AWM52 4/11/3. 1942.

Australian War Memorial. War Diary 12 Australian LAA Battery, July. AWM52 4/11/3. 1942.

Australian War Memorial. 4 Australian Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment: Training, 12 Battery. AWM52 4/11/3. October 4, 1942.

Australian War Memorial, Conqueror of the Desert. Film by Frank Hurley, Film F01825. 1942.

Australian War Memorial. Routine Order Number 40, 16 July, 1942. AWM52 4/11/3. July, 1942.

Australian War Memorial, 2/4 Australian Field Hygiene Section, Inspection: 17 August 1942, AWM52 4/11/3. August 1942.

Australian War Memorial, 2/23 Batallion. http://www.awm.gov.au/units/unit_11274.asp (accessed September 30, 2008).

Australian War Memorial. War Diary for 20 Brigade, 9th Division. October 19, 1942..

Australian War Memorial. War Diary for 20 Brigade, 9th Division, November 1, 1942.

Australian War Memorial. War Diary Summary for October 1942: 4th Australian Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, AWM52 4/11/3. October 1942.

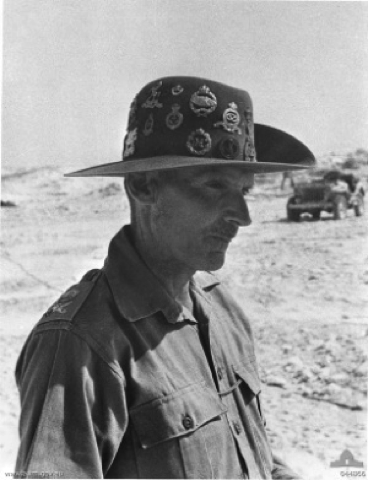

Australian War Memorial. Photograph 044866 http://cas.awm.gov.au/TST2/cst.acct_master?surl=1488051919ZZOBIQPDGAGO24299&stype=4&simplesearch=&v_umo=&v_product_id=&screen_name=&screen_parms=&screen_type=RIGHT&bvers=4&bplatform=Microsoft%20Internet%20Explorer&bos=Win32 (accessed July 21, 2008).

Australian War Memorial. Photograph P01997.009. http://cas.awm.gov.au/photograph/P01997.009

Australia’s War 1939-1945. Overview. http://www.ww2australia.gov.au/beyond/ (accessed November 2, 2008).

Australia’s War 1939-1945. Ali Baba. http://www.ww2australia.gov.au/beyond/ali-baba.html

Barter, Margaret. Far Above Battle: The Experience of Australian Soldiers in War, 1939-1945. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin. 1994.

Bianchi, Giuseppe Mario. El Alamein: Gloria nel deserto. Rome: Ciarrapico, 1991.

Boog, Horst. Germany and the Second World War: The Global War, Volume VI. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

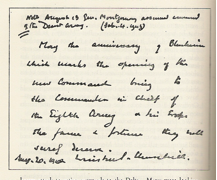

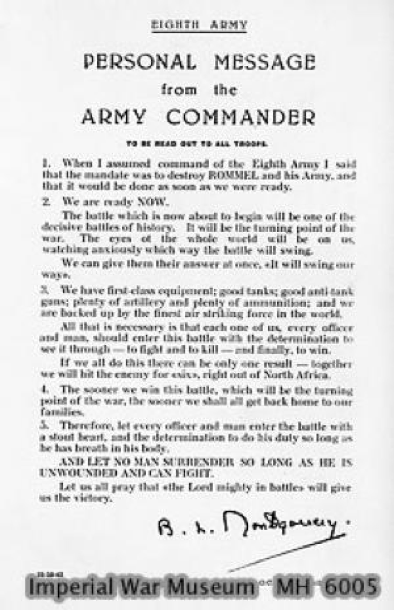

Brooks, Stephen. Montgomery and the Eighth Army: A Selection from the Diaries, Correspondence and other Papers of Field Marshal The Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, August 1942 to December 1943. London: Bodley Head, 1991.

Bruce, S. M. Cablegram to R. G. Menzies, May 1940.

Carr, E. H. What is History. New York: Vintage Books, 1961.

Churchill, Winston. The Second World War: Volume III, The Grand Alliance. 1st Australian ed. Sydney: Halstead Press, 1950.

Churchill, Winston. The Second World War, Volume IV: The Hinge of Fate. 1st Australian ed. Sydney: Halstead Press, 1951.

Churchill, Winston. The Second World War, Volume VI: Triumph and Tragedy. London: Cassell, 1954.

Clendinnen, Inga. The History Question: Who Owns the Past? Quarterly Essay. Issue 23, 2006: 1-72.

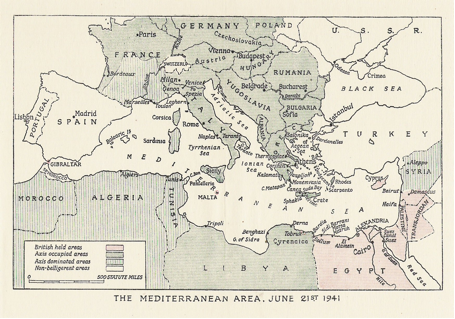

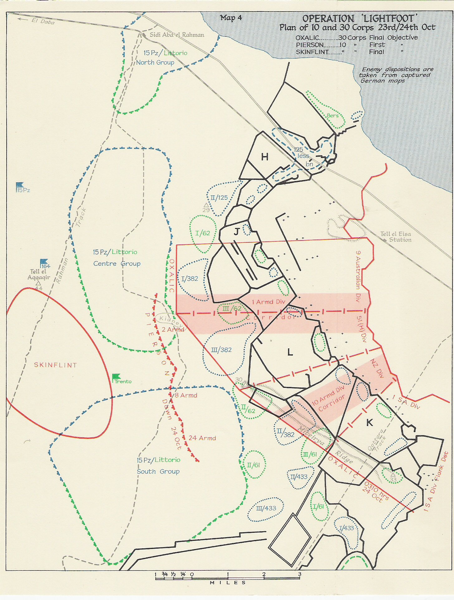

Coates, John. An Atlas of Australia’s Wars. 2nd ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Curthoys, Ann. “Thinking about History” in Australian Historical Association Bulletin. December 1996, pp.14–28.

Darian-Smith, Kate and Paula Hamilton. eds. Memory and History in Twentieth-century Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Douglas, Louise, Alan Roberts and Ruth Thompson. Oral History: A Handbook. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1988.

Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe. “Epilogue: What is History Now?” In David Cannadine. ed. What is History Now? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Hamilton, Nigel. Monty: The Making of a General 1887-1942. London: Coronet Books, 1984.

Hamilton, Paula. “The Knife Edge: Debates about Memory and History.” In Darian-Smith, Kate and Paula Hamilton. eds. Memory and History in Twentieth-Century Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Knowles, Elizabeth. Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Imperial War Museum. Photograph E18541 and E18465. http://www.iwmcollections.

Lancaster, Jo. “El Alamein, German Memorial: Conditions for Soldiers in the Western Desert.” Crete and El Alamein: IWM/AWM Study Tour 2002.

Lewin, Ronald. The Life and Death of the Afrika Korps. London: Book Club Associates, 1977.

Macintyre, Stuart.(2004) A Concise History of Australia. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maughan, Barton. Official Histories – Second World War: Tobruk and Alamein. 1st ed., Volume III, 1966.

Menzies, Robert, Speech to the nation, September 3, 1939. http://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/prime_ministers/menzies.asp

“Montgomery of Alamein, Bernard Law, 1st Viscount” Who’s Who in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press, 1999. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press.

Parsons, Max. Gunfire! A History of the 2/12 Australian Field Regiment 1940-1946. Melbourne: Globe Press, 1991.

Paterson, Michael. Winston Churchill.

Playfair, I. S. O. and Molony, C. J. C. The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Destruction of the Axis Forces in Africa: Volume IV. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1966.

Rae, C.J.E., A.L. Harris and R.K. Bryant. On Target: The Story of the 2/3rd Australian Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment. Gippsland: Enterprise Press, 1987.

Read, Alan. Australians at War Film Archive. Interview No. 1291. 2000.

Samuel, Raphael and Paul Thompson. eds. The Myths We Live By. London: Routledge, 1990.

Selwyn, Victor. ed. The Voice of War: Poems of the Second World War: The Oasis Collection. London: Michael Joseph Ltd., 1995.

Slessor, Kenneth. Beach Burial. In Victor Selwyn. ed. The Voice of War: Poems of the Second World War: the Oasis Collection. London: Michael Joseph Ltd., 1995.

Solomon, Lyle. A Gunner’s Diary. Mandurah, WA.: Smallprint Press, 2002.

Taylor, A.J.P. English History: 1914-1945. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965.

Thompson, Paul. The Voice of the Past: Oral History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Thomson, Alistair. “Passing Shots at the Anzac Legend”. In A Most Valuable Acquisition, edited by Burgmann, Verity and Jenny Lee. Ringwood: Penguin Books, 1988.

Tosh, John. The Pursuit of History. 3rd ed. Harlow: Longman, 1999.

Tute, Warren. The North African War, London: Sidgwick & Jackson,1976.

VX16838, Soldiering On, Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1942.

Ward, Russel. The Australian Legend. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1965.

West, Francis. From Alamein to Scarlet Beach: The History of 2/4 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Second A.I.F. Geelong: Deakin University Press, 1989.

Young, Desmond. Rommel. London: Collins. 1950.